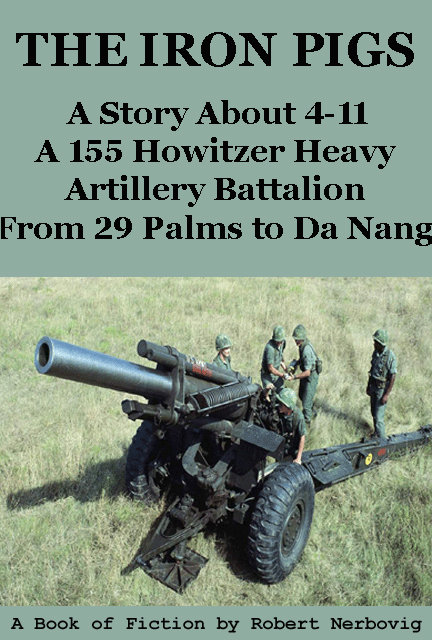

THE IRON PIGS

The high desert of Twentynine Palms doesn't know

how to be quiet. Even when the guns aren't

barking, the wind whistles through the Joshua

trees like a spent shell casing, and the heat

hums off the black rock of the Bullion Mountains.

But for the men of the 4th Battalion, 11th

Marines, the silence was always a lie. It was

just the space between the rounds.

In the Fire Direction Center, the air was thick

with the smell of stale coffee, ozone, and the

electric ionizing of the radios. It was a

windowless world of maps, grease pencils, and

slide rules. Robert sat with the headset

pressed against his ears, a lifeline of copper

wire connecting him to a Forward Observer miles

away in the shimmering dust.

"Fire Mission. Battery adjust," the voice

crackled through the static.

Robert didn't blink. He translated the

coordinates with a practiced hand, his

voice steady as he relayed the data to

the gun pits. Outside, six "Iron Pigs",

the M114 155mm howitzers, sat crouched in

the sand like prehistoric predators.

Then came the command: "Fire!"

The world didn't just shake; it

compressed. Even inside the FDC, the

overpressure of the 155mm rounds felt like

a physical blow to the chest, a rhythmic

pounding that vibrated through the marrow

of his bones. One. Two. Three. By the time

the tenth round went downrange, the desert

floor was a haze of dust and cordite.

Over four years, Robert had counted them.

Seven thousand. Eight thousand. Nine

thousand rounds. Each one was a signature

of steel written across the Mojave sky.

They were the best-trained artillerymen in

the Corps, precision-tuned and

desert-hardened. They thought the heat of

California was the ultimate test.

But as June of 1964 bled into the humid

uncertainty of the Pacific, the "Iron

Pigs" were about to find out that the

desert was a clean kind of hell. The

jungle, with its "Rocket Belt" and its

green, suffocating canopy, was waiting to

see if nine thousand rounds of practice

were enough to keep a man whole.

Robert adjusted his headset, the

high-pitched ring in his ears already a

permanent resident. He didn't know it yet,

but the echoes of those nine thousand

rounds wouldn't just follow him to

Da Nang. They would follow him for the

next sixty years.

PLEASE CRITIQUE THIS CHAPTER AT:

solartoys@yahoo.com

IF YOU WANT TO READ THE NEXT

CHAPTER EMAIL ME:

solartoys@yahoo.com

| |||||||

|

I pressed my forehead against the window and watched the Mojave open up. I was nineteen years old, fresh from training, and I had orders to the 4th Battalion, 11th Marines. 4/11. General Support Artillery. Most Marines didn't know what that meant. I barely did. But I knew we didn't carry the little 105mm howitzers the infantry could manhandle through the brush. We carried M114 155mm howitzers. Six thousand pounds of steel. Ten-man crews. Towed by tractors. The big guns. A corporal sitting across the aisle caught me looking out at the base as we rolled through the gate. "Welcome to the sandbox," he said. "Hope you brought earplugs." I stepped off the bus, and the heat hit me like a wall. Dry heat. The kind that pulls moisture straight out of your skin. The base sprawled across a flat desert with mountains in the distance that looked like rust-colored iron. Everything was brown or tan or faded green. I reported to battalion headquarters with my sea bag over my shoulder. The duty sergeant looked at my papers. "Nerbovig. Radio operator. MOS 2533." He didn't look up. "You're going to the FDC. Fire Direction Center. Stow your gear in Barracks 4. Be ready to roll in three hours. We've got night fire in the Bullion Mountains." "Three hours? I just—" "The guns don't wait," he said. "Move." By 1800 hours, I was in the back of a deuce-and-a-half bouncing over washboard roads into the training area. The dust was everywhere. In my nose, my mouth, coating my utilities, working into the threads of my boots. When the truck stopped, I jumped down and saw them for the first time. Six M114 howitzers in a staggered line. Barrels pointed at the mountains. They looked like prehistoric animals crouching in the sand. The gun crews were moving fast—heaving 95-pound shells from ammo carriers, adjusting spades, shouting over the wind. The Iron Pigs. Someone grabbed my arm. "You're FDC. Get in the tent." The FDC tent was cramped and lit by hooded lanterns. In the center was a map table covered in acetate with gridlines and coordinates marked in grease pencil. A staff sergeant shoved a headset into my hands. "Sit down, Nerbovig. This is your world now. You listen to the Forward Observer. He's out there on some ridge, cold and miserable, and he's counting on you to hear him through the static. You miss a number, and the round goes where it shouldn't. We don't miss." I put the headset on. The earcups sealed tight. For a second, there was just the hum of electronics and someone's pencil scratching on the map. Then the radio crackled. "FDC, this is Watchdog 6. Fire mission. Over." My heart slammed against my ribs. I grabbed my pencil. "Watchdog 6, this is FDC. Send your mission. Over." I wrote down the coordinates. The staff sergeant leaned over my shoulder. "Good. Now, wake up the guns." I keyed the mic to the gun line. "Battery, adjust fire. Shell HE. Fuse quick. Charge five." Then the world ended. The sound didn't just hit my ears; it went straight through my chest. Battery K fired a simultaneous volley, and the air inside the tent was sucked out. The ground under my boots liquefied. Not metaphorically. The ancient crust of the Mojave vibrated at a frequency that went straight to my bones, my teeth, my skull. "Breathe, Nerbovig!" I realized my lungs were locked. I exhaled dust and looked down at my clipboard. My hands were shaking, but the numbers were still there. "Watchdog 6, this is FDC. Shot. Over." "Shot out," came the tinny reply through the static. I sat back. My heart was hammering. I looked at the other men in the tent. To them, this was Tuesday. The plotters were already bent over the acetate, grease pencils moving like accountants doing tax returns. The Steel Symphony was just business. Over the next few weeks, the shock became a pattern. I learned that an artillery battalion was less like a group of soldiers and more like a distributed machine made of flesh, brass, and radio waves. As a 2533, I was the input. I learned to hear the difference between a Forward Observer's frantic "Fire mission!" when his unit was in contact and the slow, methodical voice of a registration mission used to calibrate the guns against desert wind. The 155mm howitzer was temperamental. I spent nights studying the technical manuals by flashlight. Internal ballistics. External ballistics. How the temperature of the powder in the breech could change the range by hundreds of meters. How the thin air of the high desert and the rotation of the earth, The Coriolis effect had to be accounted for in every calculation. "If the math is wrong, people die," the section chief told me one night as we shared a canteen of lukewarm water. "With the 105s, you miss by fifty yards, and you kick up some dust. With the 155, you miss by fifty yards, and you take out the guys you're supposed to be saving. The 4th Battalion doesn't have a margin for error." By the end of my first three months, I stopped flinching when the batteries fired. Instead, I started to feel the guns through the floor. I could tell if Gun 3 was lagging by a fraction of a second or if the powder charge on Gun 5 was running hot. I also noticed the first signs of what we called the artilleryman's tax. At night, lying in my rack in Barracks 4, the silence was never really silent. A high-pitched hum had moved into my inner ear. A faint whistling C note that sat just behind my eardrums. Some of the older guys talked about it. Most didn't. We all figured it was the price of admission. One morning during a division-level exercise, the order came down for a Time on Target mission. Every gun in the battalion, all eighteen Iron Pigs, would fire at staggered intervals so every shell impacted the target at the same second. I handled the radio for Battery L. I watched the stopwatch, finger hovering over the key. "Battery... fire!" The earth didn't shake. It heaved. Eighteen 95-pound shells tore through the air with a sound like a freight train derailing. The concussive slap hit my chest so hard it stalled my heart for a split second. I looked at my logbook. Entry number 1,042. I was no longer a boot. I was part of the machine. By the summer of 1961, the high-desert rhythm had become second nature. I wasn't checking technical manuals every five minutes. I was a component of 4/11 machine. In the FDC, my world was a constant stream of numbers, deflections, quadrants, fuse settings, flowing through my headset and onto the grease-stained maps. The training tempo accelerated until the days bled into one long concussive blur. I asn't just tracking one battery anymore. I was often coordinating fire for the entire battalion. "FDC, this is Fireball 3! Aggressor tanks in the wash! Grid eight-four-two, six- six-one! Fire for effect!" My pencil flew across the acetate. "Battery K and L, fire for effect! Shell HE, fuse quick, zone two!" Outside, the desert floor became a staging ground for mechanical earthquakes. The Iron Pigs consumed thousands of pounds of high explosives. Their barrels recoiled with a violent, oily hiss after every round. By the end of that first summer, my logbook was a testament to destruction. Five thousand rounds. Six thousand. The numbers were staggering. The high-pitched whistle in my ears wasn't just visiting anymore. It had moved in. It was a sharp, piercing frequency that sat exactly where the Forward Observer's voice used to be. I had to press my headset tighter and tighter against my skull just to hear the coordinates over the internal static of my own damaged nerves. It wasn't just the noise. It was the pressure. The 155mm howitzer generates an overpressure wave that physically displaces the air. Every time the guns fired, I felt my sinuses click and my eardrums flex. In the FDC we were slightly shielded, but the ground-slap from 9,000 pounds of pressure hitting the Mojave sand traveled up through the legs of my chair. "You okay, Bob?" a fellow plotter asked during a rare break. "You're staring at that map like it's written in Chinese." I blinked. The world tilted slightly. A wave of dizziness washed over me, a strange, fleeting sensation of being on a boat, despite standing in the middle of the desert. "Just the heat," I said, rubbing my temples. "And the ringing. It's louder today." "It's the guns, man." He lit a cigarette. "They don't just kill the target. They take a little piece of you every time they go off. But hey, at least we're the ones pulling the string." I nodded, but as I looked back at my logbook, I felt something I couldn't quite name. I was the brain of the battalion. The man who made sure the steel landed where it was supposed to. But I was starting to realize the Steel Symphony was a piece of music that never truly ended. Even when the guns were cold and the desert was still, the echo lived on inside me. By the winter of 1963, I had become a fixture of the FDC. I was no longer just a radio operator. I was the memory of the battery. I knew the habits of every gun in the line. Gun 4 tended to walk its rounds to the right if the spade wasn't set properly in the sand. The crews of Battery M were the fastest loaders in the Corps, capable of sustained fire that would melt paint off a lesser barrel. The numbers in my logbook had become a point of quiet pride. I was passing eight thousand rounds. Each digit represented a moment when I had held the line between order and chaos. In early 1964, the battalion moved out for what would be my final two-week training mission. The Iron Pigs were being pushed to their absolute limits. The rumor mill was churning. Words like "Southeast Asia" and "advisor roles" were being whispered in the mess tents, though most of us couldn't yet see the storm on the horizon. "This is the one, boys," the CO announced as we established the command post. "We're going to burn every crate of HE we've got. I want the ground to move." For fourteen days, the FDC was a pressure cooker. I worked twelve-hour shifts with the headset practically fused to my ears. The temperature dropped to near freezing at night, then rocketed to over a hundred by noon. The constant expansion and contraction of the air seemed to amplify the concussive force of the guns. It was during this stretch that the whistle in my ears turned into a roar. One afternoon, after a particularly intense three-hour fire mission, I stood up to stretch. The tent suddenly tilted thirty degrees to the left. I grabbed the edge of the map table, knuckles white. "You okay, Nerbovig?" Sergeant Miller asked. "Just... lost my footing, Sarge." The floor felt like water. I waited for the world to level out, but the horizon stayed skewed for a full minute. It was as if the 8,500 rounds I had recorded had finally shaken the gyroscope in my head loose. On the final day of the exercise, the battalion prepared for a massive coordinated strike. I was at the center of the radio net. The coordinates came in, a target area four miles deep into the impact zone. "Battery... fire!" The earth slapped. I felt the impact in my molars. I watched the clock, counting the seconds in flight. One. Two. Three... In that moment, I realized I had crossed the threshold. Nine thousand rounds. Nine thousand times, the air had been ripped apart by steel. Nine thousand times, I had been the link in the chain. June 1964 arrived with brutal, dry heat. My discharge papers were sitting in a manila folder at HQ. I spent my last day walking the gun line. The Iron Pigs were being scrubbed down, their muzzles plugged with canvas covers. I felt like a stranger in my own skin. The ringing in my ears was so loud it almost drowned out the sound of the jeep engines. I checked out of the barracks. My sea bag felt lighter than it should. I drove out the main gate of 29 Palms in civilian clothes that felt loose and unfamiliar. I looked at the mountains in the rearview mirror. I thought I was leaving the noise behind. I thought that by putting a hundred miles of desert between myself and the 11th Marines, I would finally find silence. I didn't know that the Steel Symphony wasn't something you could leave at the gate. It was carved into my inner ear. I was a 2533 for life, carrying the echo of nine thousand rounds into a world that would never be quite level again.

This site is designed and maintained by: Robert Nerbovig |